I wrote this nine years ago. I didn’t foresee AI but if I had, it would have added to the argument. See https://pvlegs.blog/2025/10/01/what-ai-cant-do-giving-students-an-ai-proof-skill/

(Larry Ferlazzo is an educator worth following. He collects, curates, and shares great ideas from educators around the world and contributes brilliant ideas of his own as well. He asked educators to predict the future, and included this comment from me. This is the last post in a two-part series. You can see Part One here. –Erik Palmer)

Response From Erik Palmer

Erik Palmer is a professional speaker and educational consultant from Denver who ran a commodity brokerage firm before spending 21 years as a classroom teacher. Palmer is the author of Teaching the Core Skills of Listening and Speaking (ASCD, 2014), Researching in a Digital World: How do I teach my students to conduct quality online research? (ASCD, 2015), and Digitally Speaking: How to Improve Student Presentations with Technology (Stenhouse, 2011). Learn more about Erik’s work at www.pvlegs.com or connect with him on Twitter @erik_palmer:

Oral communication will be by far the number one language art.

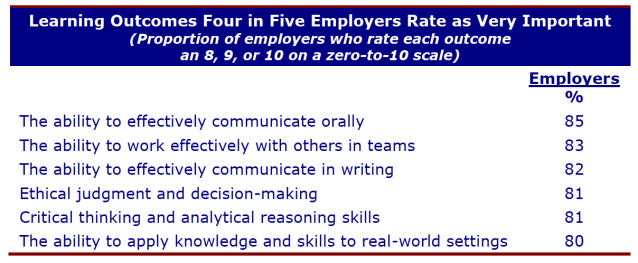

Actually, it is the most important and most used language art now, but we fail to recognize that. In the near future, speaking and listening will so dominant that it will be impossible to not realize their importance. How will people communicate? By writing? Nope, by Skype 4.0 or FaceTime 6.0 or ThisIsBetter 7.37. How will people text? By thumbing a small keyboard? Nope, by talking the message. How will people communicate internationally? By writing and email? A little, but mostly by speaking. Some will use digital tools such as WhatsApp 8.9 or GoToMeeting 11.14 or NotYetInvented 7.2. Some will speak their native language into a translation app and play the audio translation for foreign listeners. How will people get hired? By analyzing a novel well? Nope, by speaking well. The resume you speak into a resume-creating app will get you in the door, but your speaking will get you the job. The hiring process will involve digital speaking tools: interviews are now being done over Skype; voice-analyzing software will be a big part of hiring decisions. How will people write? By typing on a keyboard or mobile device? Nope, by speaking into voice-to-text apps. How will we research? By verbally asking a device a question and listening to the answer. You can read more of my predictions here.

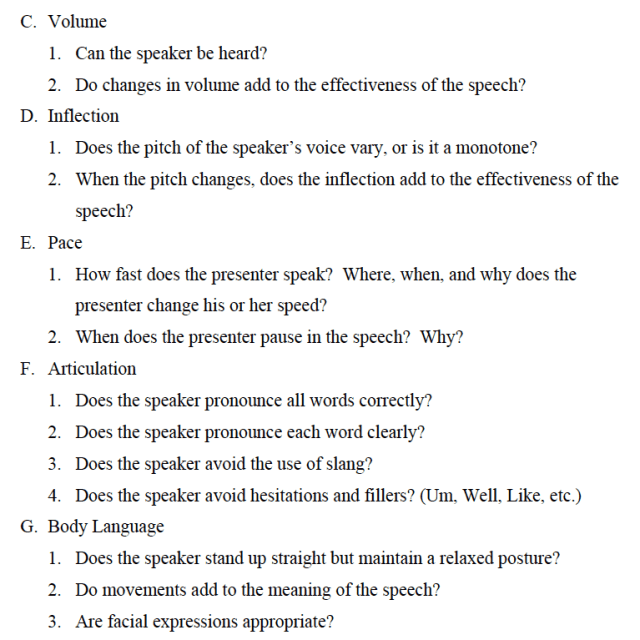

Of course, all of those are happening now so it is not very bold to suggest that our future will see more verbal communication tools and an increase in their prominence. What is bold is say that we should decrease emphasis on haiku and increase emphasis on speaking. No one will ever say, “Palmer, fire off a haiku to our affiliate in Beijing,” but every day of our lives how we speak will matter. Oddly, my son had haiku units in five different grades but never had one oral communication unit. Yes, after the haiku unit, he was asked to get up and say a haiku poem, but he was never taught how to say that poem well. Lessons about word choice, yes. Lessons about syllables, yes. Lessons about where to put commas, yes. Lessons about adding life to the voice, no. Lessons about speeding up and slowing down for effect, no. Lessons about descriptive hand gestures or body gestures or facial gestures, no.

It is already true that the odds of professional and social success dramatically improve if you are well spoken. In twenty years, those who speak well will have an even bigger advantage. At some point, schools will be forced to pay attention to this reality. The favorite lessons teachers have trotted out for the last fifty or sixty years will go away, and curricula will be adjusted to specifically teach the most important language art, speaking, as much as the language arts of reading and writing.

Copyright Erik Palmer