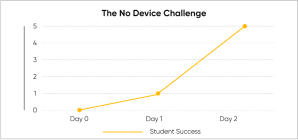

Should you have students make podcasts? It’s a great idea for students in second grade (yes, second grade!) through twelfth grade for several reasons:

- Making a podcast provides a break from traditional writing and speaking activities.

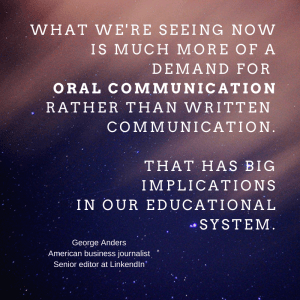

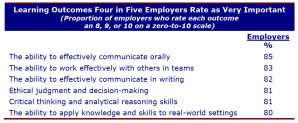

- Podcasts give students practice speaking, a critical skill in a world where oral communication is more important than ever. Providing practice with speaking is especially valuable for multilingual learners.

- Podcasts give all students a chance to shine. You have many students who struggle when reading and writing but thrive when speaking. Podcasting plays into their strength.

- Podcasts give voice to the shy. You have students who don’t feel comfortable speaking in front of an audience. A podcast allows for recording, re-recording, and re-re-recording in the safety of the “studio” until the message is one they want to share.

- Podcasts can give students a wider audience. When the audience is always the teacher and the classmates, enthusiasm wanes. But a podcast that may be heard repeatedly around the school? For many, that is motivating and exciting.

- Podcasts can help teach media literacy, specifically the language of sound. How is sound used to enhance messages? How can sound can be used to manipulate listeners?

- Podcasts are real life. Your students know about them. Your state speaking and listening standards include them. In my state, Colorado, beginning in second grade, students are expected to make audio recordings.

- The process of creating podcasts involves several skills, and one big payoff is that it gives students an authentic reason to read and write.

Bottom line: podcasts are worth adding to your curriculum.

Why Do Podcasts Exist?

But let’s back up for a minute. Why do podcasts exist? To create and distribute the spoken word through audio files. In other words, they showcase speaking. Speaking may be telling stories, reporting on news, sharing an opinion, and more, but the essence of podcasting is speaking. Yes, as we will note later, sounds may be added to that speaking, but the point is to let others listen to you talk.

When you listen to the student podcasts that have been created by teachers in the technological vanguard, it seems many of us have missed this key point. To be blunt, most student podcasts out there are pretty lackluster. We put the tools first and forgot that we should put the message first. We have recorded and published very rough drafts that didn’t include the skills needed to develop and perform the messages that were recorded. Let’s look at some simple, easy-to-teach things we can share with students to enable them to make podcasts that are engaging and worthwhile.

Before Recording

Teachers should begin by creating a space where students feel comfortable recording themselves. Organizing a script first that plans out who is talking and exactly what they’re going to say might be helpful. Sentence starters, visual aids, or other tools may help students who need additional support creating a script. Feel free to use our script organizer template from Into Literature when planning your lesson.

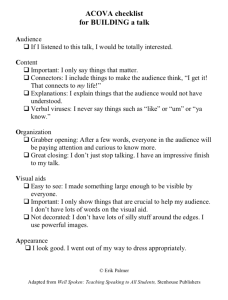

With that in mind, let’s examine how to create better podcasts. I have written elsewhere that all speaking involves two distinct parts: what you do before you speak and what you do as you speak. In the world of podcasting, it can be thought of as before you hit record and as you are recording. What should your students do before recording? I’ll mention two ideas: analyzing the audience and adjusting content.

We don’t often ask students to analyze their audience. We give them a checklist of what to include.

- Second-grade country reports: “Italy is 116,000 square miles. The population is 59 million. The government is a parliament. The export is packaged medicaments. A famous person is Dante.”

- Eighth-grade book talks: “The main character is . . . the setting is . . . the climax is . . . the secondary character is. . . .”

- Eleventh-grade social studies report: “95% of high school students use social media and 35% use social “almost constantly.” Being on social media for more than 3 hours per day doubles the risk of experiencing poor mental health outcomes, including symptoms of depression and anxiety.”

Students dutifully tell us what we asked them to include, but their peers are unimpressed by such talks. Our checklists leave off something critical. Students are seldom asked to think about the audience: What are their interests? How can you make this come alive to them? What would they be interested in hearing? What would make them sit up and listen? (This is a lesson needed before all talks, not just podcasts.)

Decide where the podcasts will be shared, for example on a class website, then help students focus on who the full audience is. They are probably more diverse than a classroom of peers. Family members? Students from other classrooms? Students from other grades? Think about them. Are they expecting something formal or casual? Is switching between languages appropriate? What is the big picture of the audience? Then, using our examples, how can I make this country/book/social studies topic interesting to all of those listeners as I focus the discussion? What can I include to engage parents and family members? What should I explain to help students in different grades understand? What should I add to make a list of statistics meaningful to listeners? The checklists and rubrics we give students need to include targeting the audience in order to sustain interest in a world where more engaging content is a click away.

Connecting to the Listener

Once you understand the audience, adjust the content further by adding elements that will engage the listener. First, develop a powerful opening. The very common “Hi, my name is Erik, and my book is Worser” probably doesn’t grab the listener’s attention. Teach students how to create a compelling opening.

- “Do you love pizza? It came from my country!”

- “Have you ever felt like you didn’t belong? Have you wanted to be different than you are? Worser had those problems and one huge additional one.”

- “Sleep problems. Anxiety. Constant distractions. Online bullying. Fun stuff, right? But I can tell you how to avoid those.”

Next, add content that answers the questions in the paragraph above. What will connect with the listeners’ lives and make them want to hear more? Rethink what a country report, a book talk, or a social studies talk should include. What fun facts will make Italy come alive? What story from the book will impress the listeners? What stories about social media use will help us understand the issues? Again, typical checklists and rubrics will need additions.

Finally, end well. “And that’s my report” is common . . . and boring. What will leave a lasting impression on the listeners? “I’m 16. I want to make my own choices about my life. I don’t want to be controlled by social media. You can make your own choices, too.”

During Recording

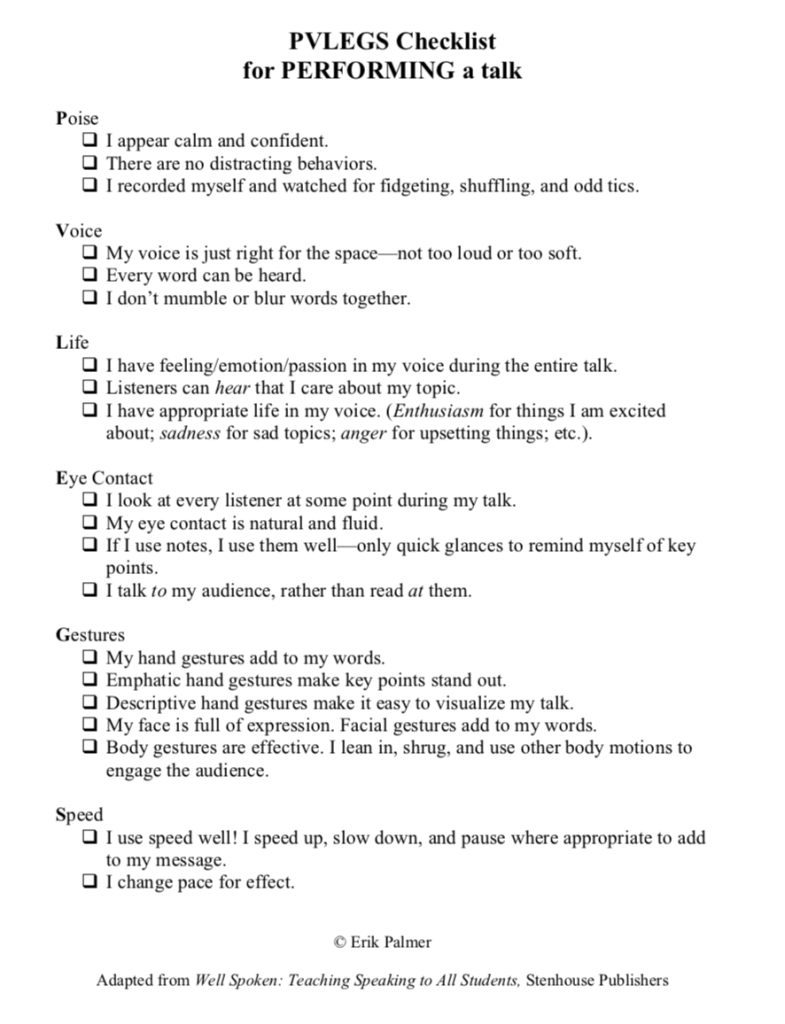

Designing for the audience and improving content, while crucial, will not make a winning podcast. It is important to give students instruction about what to do as they record as well. Performance matters. Teach students how to make their voices command attention.

At a minimum, stress that every word needs to be heard. Podcasts demand careful enunciation and volume control. The audience may be listening to the small speaker of a cell phone with ambient noises of the city or a small tablet speaker with all the distractions of home around them—barking dogs, TV in the background, and more. “My name is Erik and thank you for joining us. Today’s topic is . . .” becomes “My namezerik and thainkoo furjoiny us. Taze topic is. . . .” Quiet mumbling is not going to compete in a world of permanent partial attention. And speaking of ambient noises, make sure none of them affect your recording. A quiet recording space is imperative. If you decide to add sound, be very careful about what sound to add. The looping 15-second music clip available on the podcast tool is always a mistake. What music, if any, would add to the message and where should it be added? Non-stop music is not needed. And what volume level avoids drowning out the words? Record. Listen. Re-record. Never assume one take will suffice.

Speaking with Life

Making sure that every word is heard is the minimum. Great podcasters speak with lots of life. Inflection, expression, intonation, and pitch might be confusing terms to students and can be avoided. Instead, make it clear that they need life! We should hear excitement, sadness, surprise, concern, and happiness where appropriate. Speaking with life is the number one growth area for all speakers. Students may be lively in the hallways, but the poetry recitations are flat and uninteresting. I use phrases that demand life as practice activities for students to see how adding life is important for a message’s impact:

- “The three richest Americans have more wealth than the bottom half of the United States.”

- “You used my toothbrush to brush the dog’s teeth?”

- “Run! They’re gaining on us!!”

Then, I ensure that voices are full of life as students record. Record. Listen with new ears. Don’t accept, “They’re just kids, so of course it isn’t very good.” Expect more, and students will deliver more. Look for places to add life. Re-record. After every practice, raise the bar a bit more until listeners will think, “That kid is a skilled talker!”

Finishing the Podcast

Yes, we could say more about how to create and perform, but this is a good start. Now, you are ready to use the tools available. Younger students may need nothing more than a website such as Vocaroo, access to a cell phone with a built-in voice recorder, or the QuickTime player app on the school computer. A web search will reveal many other ways to record audio. Older students may surprise you with their tech abilities and will know how to use GarageBand and similar tools, along with the editing and sound-enhancing elements they include. Upload to whatever platform your school uses.

You can help end boring podcasts. Redesign the checklists and rubrics you have always used for in-class assignments to make them podcast-specific. And teach speaking! Give students explicit instruction about how to be livelier, more engaging speakers. With a script worth recording and some lessons about how to speak impressively while recording, students will be poised to create amazing podcasts. A message-first approach instead of a tool-first approach will make podcasts worth a listen.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of HMH.

***

Blog contributor Erik Palmer is a program consultant for Into Literature, HMH’s curriculum for creating passionate, critical readers in Grades 6–12.

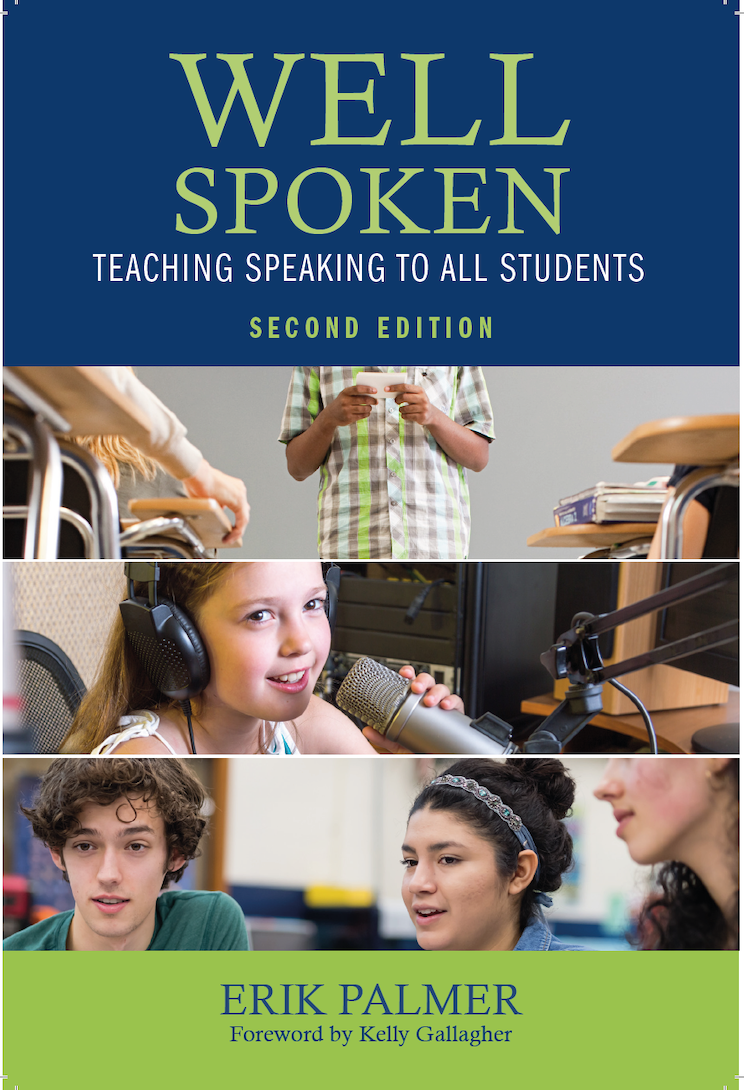

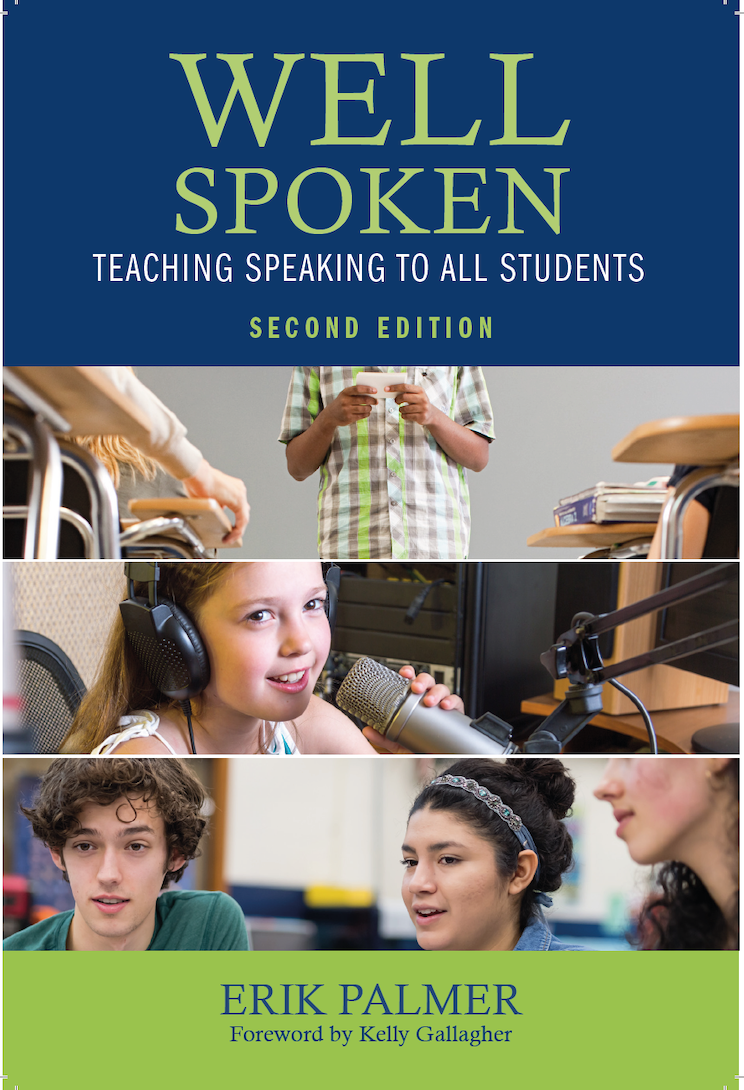

The non-stop focus on readinganwriting–the words are so commonly put together that they might as well be blended–fails to give students real voice. I understand that you love reading novels and writing poetry, but your students need to be taught how to be effective speakers. It is not an innate ability and requires direct instruction.

The non-stop focus on readinganwriting–the words are so commonly put together that they might as well be blended–fails to give students real voice. I understand that you love reading novels and writing poetry, but your students need to be taught how to be effective speakers. It is not an innate ability and requires direct instruction.