I want all students to become better speakers.

Every time I say that I get a response like “Oh yes, public speaking is so important!”

I really dislike that response. Let me explain.

The words have a terrible connotation. “Public speaking” is one of the most loaded phrases in our language, and lots of baggage comes with those words. We all know that public speaking is feared. The cliché is that people fear public speaking more than death. This is obviously absurd. Given a choice between going to a microphone for five minutes or getting killed, everyone would choose speaking. But the damage has been done:

public speaking = horrible experience

Convincing teachers to spend time teaching speaking is harder when I start in such a deep hole. Teachers want to protect students from painful things.

The words limit our understanding of what speaking is. All speaking is, in a sense, public. Unless you are muttering aloud to yourself at home, your speaking is heard by others and is done in public. Whether in a school, a restaurant, a staff meeting, or a store, if someone can hear you, you are speaking publicly. I don’t expect to get agreement that the common definition of public speaking should change, however. I know that “public speaking” makes people think of some formal speech in front of a large crowd.

But I didn’t say I want all students to become better at public speaking, I said I want them to become better speakers. Public speaking as people think of it is one tiny aspect of speaking. A couple of times in life, we may be called upon to do that kind of talk—wedding toast or eulogy perhaps—but we do so many other kinds of speaking every day. Think of the speaking you do. Some of it is one-to-one, small group, informal, in-person, or via digital tool; some is to family, friends, co-workers, students, or parents. You talk in many situations. I want to prepare students to succeed in all of those.

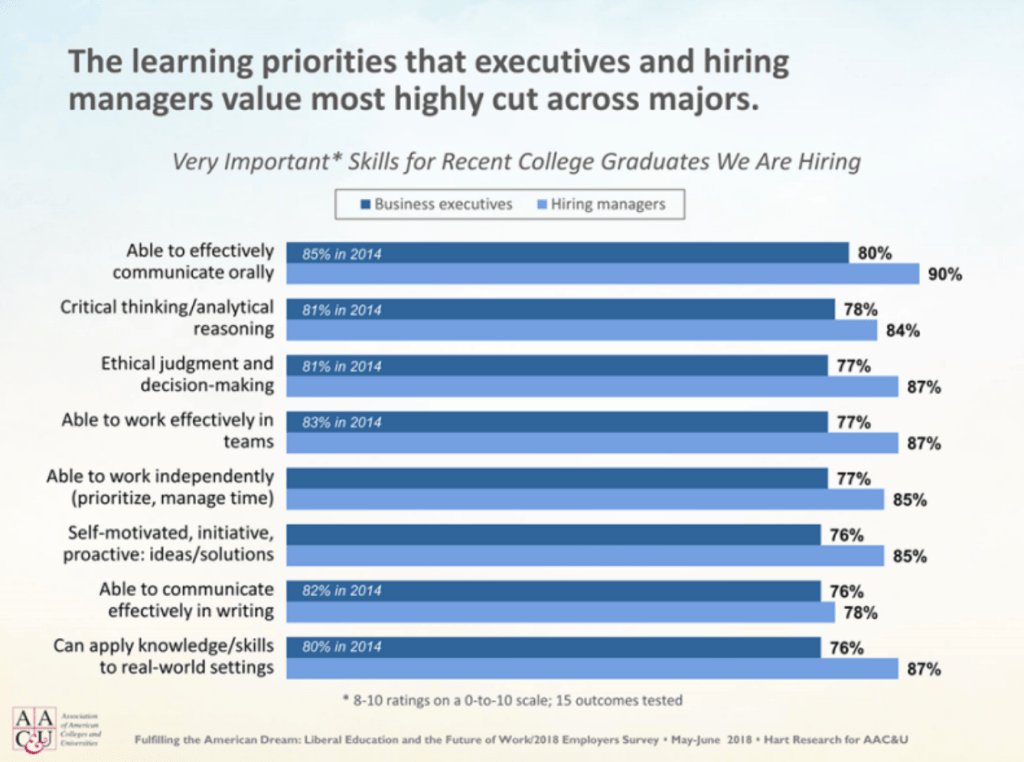

Oral communication is always at the top of the list of skills employers want. The 90% of hiring managers who say that speaking is a very important skill (see chart) aren’t looking for public speakers. They want employees who are generally well spoken. Yes, some jobs involve occasional presentations, but all jobs involve talking. Whether collaborating with co-workers, attending to customers, or fielding client calls, effective speakers are in demand. If we look at oral communication the way the business world does, we realize that speaking is an incredibly important language art for professional success. To conflate “speaking” with “public speaking” causes us to seriously undervalue the need to teach verbal communication skills. It allows us to pretend that speaking will not be important in the lives of most students: few will be public speakers so why teach speaking?

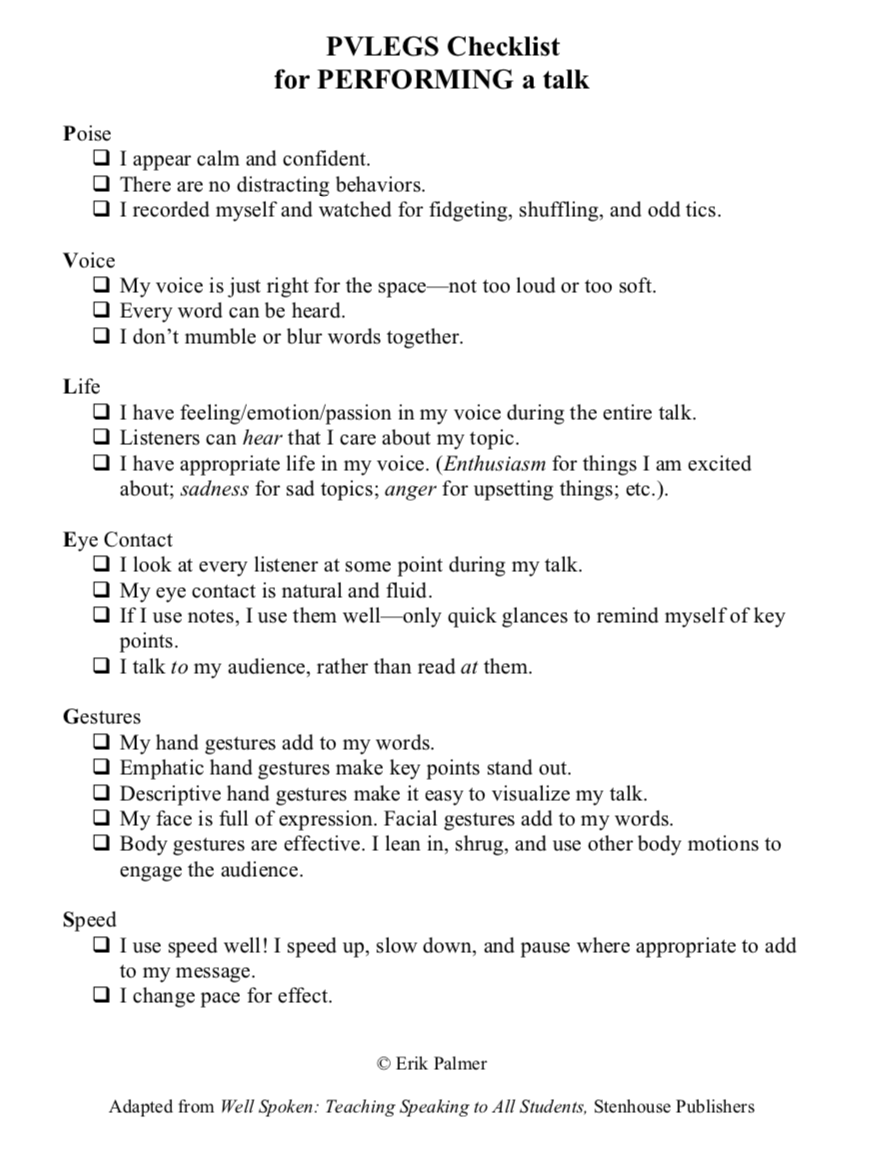

The words make us think about speaking incorrectly. “Speak loudly.” That’s one common response when I ask teachers to tell me specific things that students should do to be good speakers. It is probably poor advice in any situation—you would hate it if a speaker was always loud. In any event, it is a comment that would only apply to public speaking. Remember, I want students to be good speakers across the entire spectrum of oral communication. Speak loudly at a co-worker? Not a good idea. If we think only about public speaking, we will not correctly think about the skills needed for being a well-rounded communicator. In the framework I developed, I replace “speak loudly” with “make every word heard.” That’s it. Good speakers make sure that listeners hear them and that the voice is just right for the space. In a gymnasium, we speak more loudly; on a Zoom call, we adjust the microphone; on a romantic date, we speak softly. In each case, all we want is for every word to be heard. Note that this instruction applies to all types of speaking.

Consider a comment like “Use good grammar.” That doesn’t apply to every situation, either. In the dugout, “That ain’t a strike, ump” works better than “I don’t believe that was a strike, umpire.” Good speakers don’t always use good grammar. They adjust language for the situation and the audience. Adjusting language also applies to all types of speaking. Effective public speakers make every word heard and adjust language for the audience. So do new parents talking to their baby and graphic designers showing their portfolios to prospective employers. Thinking only about public speaking leads us to offer advice that doesn’t apply generally whereas true speaking tips prepare students for all forms of oral communication.

I know I am fighting an uphill battle. I say “speaking” and most people instantly think “public speaking.” But now you know better. Let’s think about speaking broadly, correctly. Let’s give all students an effective voice. Let’s create well-spoken people who are confident and competent verbal communicators in every oral communication situation.

Contact me at https://pvlegs.com/contact/ and I’ll send you a free book.