Millions of Americans do not believe Joe Biden was elected president. Every election until now reported results and every citizen accepted that those results were accurate. How did we get to a point where millions of us do not believe what has been proven over and over?

Because while you were teaching students to not believe fake stories, Donald Trump was teaching Americans to not believe true stories.

Beginning five years ago, Donald Trump criticized the media, targeting specific people, networks, and papers. Initially, he picked on the New York Times and CNN. Now, even Fox News is on his hit list (see an article here). Originally, almost all news sources were called “fake news” by the former President. Then they became enemies of the American people. Attacking the press was a key part of his presidency from the early days.

All reporting is wrong. Don’t believe anything. Those were the messages received non-stop.

But is it dangerous to destroy belief in the media?

MISUSING THE WORD “FAKE”

Fake means false. Didn’t happen. Reporting that a poll that says 32% of the people trust the media is not fake if in fact such a poll existed. That some other poll might have different percentages does not mean that the first story was fake. CNN, ABC, NBC accurately reported the polls in the election. That the election turned out differently does not mean the stories were made up.

Not covering a story or only covering part of a story does not equal fake news. If there were big crowds on one side of the street supporting Black Lives Matter and counter protestors on the other side of the street, showing only one side of the street is misleading. Ignoring the other side of the street may be evidence of bias, but bias does not mean fake. The people shown were actually there. There is a huge difference between choosing one view over another (bias) and reporting something that never happened (fake). Pointing out bias is fair. Denying the truth is sinister.

THE PROBLEM IS NOT WHAT YOU THINK IT IS

Our first response to “fake news” as educators was to teach students how to sniff out fake news. We pointed out that some stories were totally false. Made up. Never happened. No truth. We wanted to give kids tools for figuring out which stories were fabricated. But teaching students how to find lies has turned out to be a much smaller problem than the frightening issue with “fake news”:

I am a little worried that students will believe something that is false.

I am terrified that students will not believe something that is true.

While we emphasized the small amount of stuff that is nonsense, we missed the incredibly serious risk of creating cynics who feel comfortable disregarding truths. One of the most important pieces of civil society was undermined while we were watching. Millions of us do not believe that which is true.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE PRESS

A little history. Within minutes of creating a new country, our Founding Fathers decided to make ten changes to the Constitution. The very first change they proposed?

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Amendment 1 protects freedoms of religion, speech, press, assembly, and petition. The Founders were worried that these freedoms, not specifically mentioned in the articles setting up the government, could be attacked. Before anything else, they wanted to guarantee these freedoms.

…the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable. James Madison

Our liberty depends on the freedom of the press, and that cannot be limited without being lost. Thomas Jefferson

The Founding Fathers realized that a free and respected press would help hold government leaders accountable, publicize important issues, and educate citizens so they can make informed decisions. Attacking the press, then, is a very dicey proposition. If the press is demeaned, those three things don’t happen. Who will perform those functions? This is not a liberal or a conservative issue. Both ideologies agree that a free press is critical to a well-functioning democracy.

Yet if our right to a free and independent press is infringed, all other rights fall. Our ability to be informed and the free flow of information, regardless of how damaging it is to elected officials, is one of the most essential safeguards to our liberty. The fight for a free press is one that we absolutely cannot afford to lose. http://www.freedomworks.org/content/flashback-founders-necessity-free-press

The press, which is essential to the preservation of liberty, has also come under attack from the government. One of the principles that ensures a free press is that journalists are not required to reveal their sources. This is one way government whistleblowers can feel free to come forward and reveal information that is of public importance, such as governmental corruption and abuse, without fearing exposure. If journalists were required to reveal their sources, scandals involving government corruption and wrongdoing such as Watergate might never be brought to the attention of the media and, thus, the American people. https://www.rutherford.org/constitutional_corner/amendment_i_freedom_of_religion_speech_press_and_assembly

DESTROYING FAITH IN A CRITICAL INSTITUTION

The non-stop barrage of “fake news” had an effect. Distrust in the media is increasing. From Gallup analyst Art Swift:

Americans’ trust and confidence in the mass media ‘to report the news fully, accurately and fairly’ has dropped to its lowest level in Gallup polling history, with 32 percent saying they have a great deal or fair amount of trust in the media. http://thehill.com/blogs/blog-briefing-room/296003-poll-trust-in-media-at-all-time-low

The numbers are radically different based on party affiliation: 14% of Republicans, 30% of independents, and 51% of Democrats trust the media. According to an Emerson College poll, 91% of Republicans think the news media is untruthful (47% of independents, 31% of Democrats). http://thehill.com/homenews/media/318514-trump-admin-seen-as-more-truthful-than-news-media-poll At the extreme, Trump supporters shouted “luegenpresse” at a rally (see the article here).

In other words, Trump’s strategy worked. That many Americans do not believe that the 2020 election results are real and that COVID is a hoax proves it. It’s all fake news and there are no longer accepted facts.

EDUCATORS MUST RESPOND

It is not enough, then, to teach students how to ferret out falsehoods. It is critical, yes, but more is needed. We must set the context. We must explain the importance of a free press. We must explain the core principles of our Founding Fathers. We must point out how rulers around the world and throughout history have attacked the press in order to subjugate the citizenry. We must make clear that a free press is never the enemy of the people. And yes, we have to risk upsetting some people by making clear that Trump was frighteningly wrong.

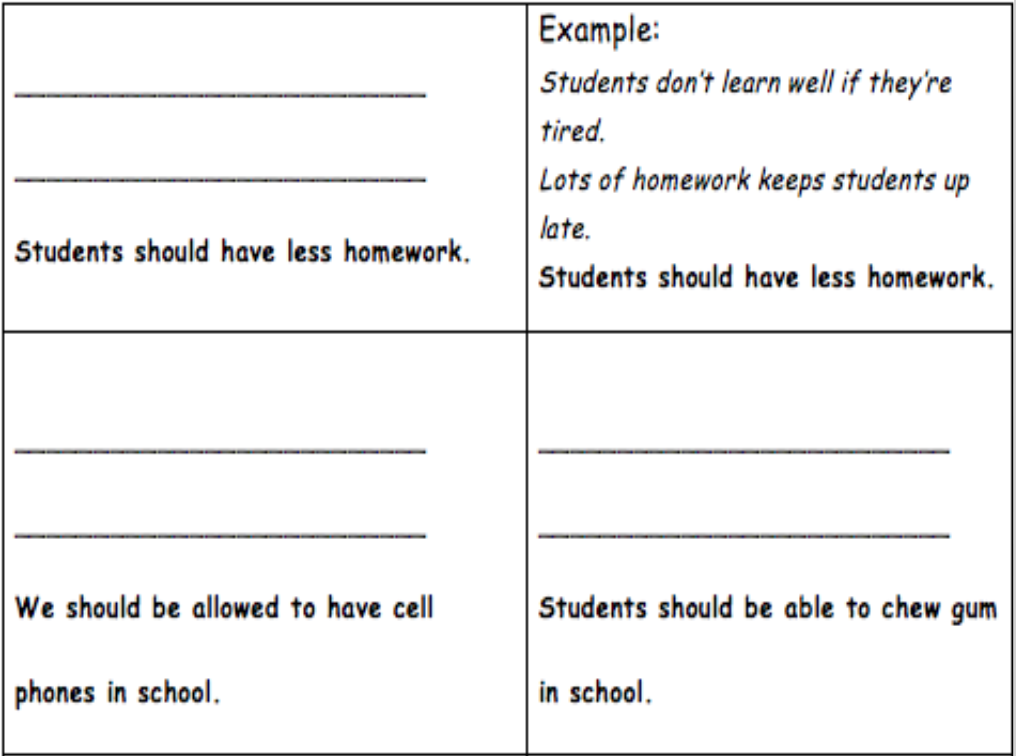

The first one is a completed example. Students can fill in the others. Note: there is no one answer. One student could say, “Students can’t think well when they are fidgety. Recess gets rid of fidgety. So we need more recess.” Another might suggest, “Childhood obesity is a problem. Recess provides calorie burning activity. So we need more recess.” In some cases, a statement is offered and students need to come up with another statement and a conclusion. Again, there is no one answer. “The U.S. spends billions on defense. We have never been invaded. Therefore, we should keep spending.” Or, alternatively, “The U.S. spends billions on defense. Lots of that money is wasted. Therefore, we don’t need to spend that much.”

The first one is a completed example. Students can fill in the others. Note: there is no one answer. One student could say, “Students can’t think well when they are fidgety. Recess gets rid of fidgety. So we need more recess.” Another might suggest, “Childhood obesity is a problem. Recess provides calorie burning activity. So we need more recess.” In some cases, a statement is offered and students need to come up with another statement and a conclusion. Again, there is no one answer. “The U.S. spends billions on defense. We have never been invaded. Therefore, we should keep spending.” Or, alternatively, “The U.S. spends billions on defense. Lots of that money is wasted. Therefore, we don’t need to spend that much.”