Voices from the Middle, Volume 22 Number 1, September 2014

The Forgotten Language Arts:

Addressing Listening & Speaking

Erik Palmer

TEACHING THE COMMON CORE

The Forgotten Language Arts: Addressing Listening & Speaking

ABSTRACT

Common Core State Standards include listening and speaking standards yet those receive little attention. All teachers need to become aware of the requirements of the standards and need to specifically teach students the skills needed to master the standards. There is much more to the standards than the words “listening” and “speaking” suggest. Students must learn how to collaborate with diverse partners, evaluate information from diverse media and in diverse formats, evaluate speakers’ rhetoric, construct and deliver presentations, incorporate multimedia in talks, and adapt speech to varied contexts. This article introduces the standards and suggests approaches to mastering them.

TEACHING THE COMMON CORE

The Forgotten Language Arts: Addressing Listening & Speaking

Common Core State Standards (CCSS; National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers, 2010) have been the major topic of discussion for some time now. English teachers are probably aware that ELA Standards have led us to examine the fiction/nonfiction percentages in our classes, the text complexity of our materials, and the meaning of close reading. Most teachers, however, still seem to be unaware of the listening and speaking part of the Standards. Test yourself:

- How many listening and speaking standards are there?

- What is the category name given to the three “listening” standards?

- What is the category name used for the three “speaking” standards? (Question one answer revealed! Six!)

- What is the general idea of each of the six standards?

Don’t panic if you missed some (or all). The odds are overwhelming that your school has not focused on these. Perhaps they have never been mentioned. You never had a workshop or inservice presentation about them. You most likely have no materials on hand about how to address them. Even materials that offer help with Common Core Standards overlook listening and speaking. For example, there are four ELA Standards (reading, writing, speaking & listening, language), so you might expect a book such as Pathways to the Common Core (Calkins, Lehrenworth, Lehman, 2012) to spend a quarter of its pages on each topic. In fact, the speaking and listening section is less than 5% of the book. Shortchanging these Standards is common.

Do panic if you don’t remedy these situations. Students cannot master the Common Core Standards without mastering these specific Standards. And for those of you in areas where Common Core Standards are losing favor, know that students cannot be prepared for life without mastering these Standards. If the Common Core movement goes away tomorrow, these six parts of that movement must remain.

I am afraid that when teachers become aware that listening and speaking Standards exist, they will think, “Oh, I’ve got those covered. I don’t have problems with classroom management and my students do lots of talking in class.” We confuse sitting still and being quiet with effective listening; we mistake having the ability to utter words with effective oral communication. I make the argument in Teaching the Core Skills of Listening and Speaking (Palmer, 2014) that there is much more to the Standards than the words “listening” and “speaking” suggest. Let me share a part of that here.

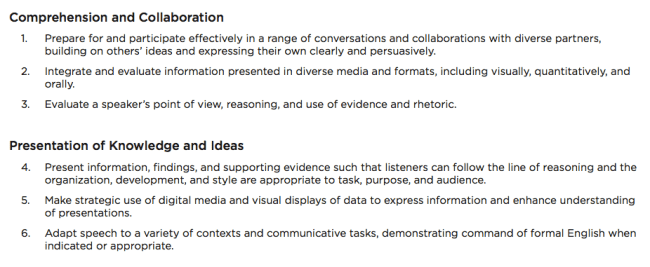

To answer the second question above, the “listening” Standards actually fall under the label “Comprehension and Collaboration.” As you look at the three Standards under this umbrella, two points will stand out: there is not one of these that we wouldn’t want for all students; there is much more involved than the word “listening” would suggest.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.1: Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.2: Integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.3: Evaluate a speaker’s point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric. (CCSS, 2014)

To meet these Standards, serious instruction is required. Standard 2, for instance, requires us to teach sound (how it can be used to manipulate us and/or enhance presentations); to teach images (the importance of image selection and how images convey story); to teach video (the reasons for scene selection, camera angle, montage, and so on). We probably underuse diverse media in our classrooms. We definitely fail to teach all students how to analyze the construction of multimedia messages and how that construction contributes to the underlying message.

Standard 3 requires us to teach reasoning (e.g., understanding ad hominem attacks, hasty generalizations, cause/correlation errors), logic (e.g., looking for premises that will lead to the conclusion), and rhetorical devices (e.g., hyperbole, repetition, persuasive techniques). These are teachable, yet you will find few English teachers with persuasive technique units or logic lessons. Students cannot figure these things out on their own, just as they cannot figure out metaphors without direct, specific instruction. Brilliant use of metaphors, good reasoning, and the ability to analyze images do not spontaneously occur. They all require specific instruction. Why, then, do we only teach about metaphors? How can students evaluate diverse formats without specific media literacy lessons?

It is not difficult to teach these new skills. For example, here’s a simple lesson on the power of images: Give one team of students a camera and instruct them to make the school look terrible today; give another team a camera and instruct them to make the school look great today. Both will succeed. One team will photograph trash that missed the wastebasket, a torn poster hanging on the wall, and so on; the other, smiling students, the newest computer in the library. It is quickly obvious that images have power to tell stories and that image selection is important. Both groups told the “truth,” yet the messages are quite different. Students will now be critical of the images they are exposed to in the information they receive. Now we are on the way to mastering Standard 2. As I noted, it is not difficult to teach the skills. It is very difficult, however, to open our minds to the reality that haiku may have to move aside to allow instruction about new literacies.

My passion has always been oral communication—giving students the ability to communicate well in any situation. I fear that if teachers think of speaking skills at all, they think of Public Speaking, that one big presentation. The Standards correctly value developing oral communication skills for all verbal communication situations including, but not limited to, formal presentations.

Look at the three Anchor Standards for “speaking” or, more correctly, “Presentation of Knowledge and Ideas”:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.4: Present information, findings, and supporting evidence such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning, and the organization, development, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.5: Make strategic use of digital media and visual displays of data to express information and enhance understanding of presentations.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.6: Adapt speech to a variety of contexts and communicative tasks, demonstrating command of formal English when indicated or appropriate. (CCSS, 2014)

In a recent issue of Language Arts, a teacher described a project she did with her class. She included a grid where she checked off the many Standards met by the project. Because she had students present results to the class with a PowerPoint at the project’s end, she checked off all three speaking Standards and said, “Students met many of the speaking and listening Standards when they presented their findings to their peers” (Grindon, 2014).

In fact, it is possible that they met none of them. There was no evidence that any student spoke well, as Standard 4 would require. Standard 5 requires incorporating multimedia, audio, and video. Bullet points on a PowerPoint slide do not qualify. Standard 6 requires the ability to adapt speech to a variety of audiences. How does talking one time to a group of peers demonstrate that ability? Additionally, this teacher made a mistake almost all teachers make: failing to understand that assigning a speaking activity is not the same as teaching students how to do that activity well.

Imagine this scenario: a teacher is asked how he teaches writing. He replies, “At the end of some reading assignments, I tell kids to write for five minutes.” You ask him if ever teaches about punctuation, capitalization, sentence structure, or word choice, and he says, “Not exactly. I put some of those terms on the rubric, but I don’t have any particular lessons on them. I guess I think the kids will just figure out how to be a good writer somehow. They wrote for five minutes so I checked off all of the writing standards.” You would be appalled and rightly so. Commonly, though, teachers have students talk as an afterthought to some assignment, yet offer no lessons on the skills they assess. Look at the score sheets that you use in your class for speaking activities. Can you point to specific instruction you gave to students for each of the criteria? If you score “presence,” can you tell us exactly how you taught that? How about “body language”? When did you teach that?

Standard 4 requires students to construct a speech and to deliver it. (The expectations for delivery are quite low, as you will discover when you look at grade-level Standards.) Certainly, we see a tie-in with writing instruction (content, organization, voice), but it is important to realize that an effective oral communication is more than a good essay muttered aloud.

Standard 5 will stretch us. Very few teachers require video and audio enhancements in talks, and almost none of us had instruction about how to create videos, let alone how to teach those things. Camera angles, editing, adding sound? Teaching students how to incorporate media into presentations will be difficult. Suggestion: Use your students as a resource. Many students have been creating multimedia presentations on their own and are proficient with tools teachers are not aware of. Let students lead the way and then offer them guidance about matching style to substance.

Standard 6 expands our ideas about “acceptable” speech by forcing us to recognize that effective talks are adapted to the audience. English teachers always emphasize good grammar, but effective communication can occur without it.

Again, these are teachable skills. For example, to teach Standard 6, start with a discussion. Ask students if they speak differently to grandparents than to friends. What is different? Why? Point out that intuitively, we adjust speech. Then, offer a small assignment. Have students tell about something that happened at school in three different ways: as you would tell it to peers outside of school; as you would tell it to grandma; and as you would tell it to a newsperson interviewing you for the nightly news. Language will be different, formality levels will be different. Finally, adjust audiences during the year. Assign a presentation to be given to the class; bring in parents for some talk; make an instructional video to post on YouTube. For each, explicitly discuss the adaptations needed to be effective in the situation. I know I am on thin ice when I seem to attack haiku, but again I suggest that it may need to be de-emphasized to make room for these important skills.

We work hard to improve every child’s ability to read and to write. We must commit to working equally hard to improve every child’s ability to work well with others, to evaluate the diverse messages received, to create an engaging presentation, and to speak well in all situations. These are crucial skills. Common Core Standards give us a push, but concern for our students’ future should provide the motivation.

References

Calkins, L., Ehrenworth, M., & Lehman, C. (2012). Pathways to the common core. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Grindon, K. (2014). Advocacy at the core: Inquiry and empowerment in the time of common core state standards. Language Arts, 91, 251–266.

National Association of Colleges and Employers. (2012, October). Job outlook 2013. Bethlehem, PA: Author.

National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010). Common core state standards for English language arts and literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/ela-literacy.

Palmer, E. (2014). Teaching the core skills of listening & speaking. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Palmer, E. (2011). Well spoken: Teaching speaking to all students. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

By Erik Palmer

By Erik Palmer